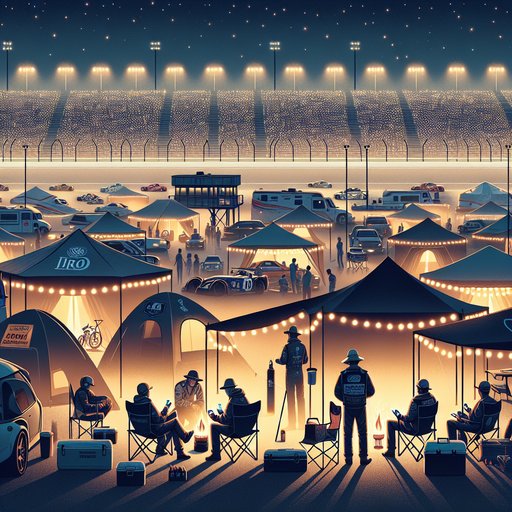

Rally spectators form a distinctive subculture that treats remote forests, mountains, and deserts as grandstands. They tolerate weather, long hikes, and limited amenities to watch cars at full speed on natural roads—often just meters away—while respecting strict safety rules that keep the sport accessible.

Rallying runs on closed public roads, so the venue is the landscape itself. Fans trek to gravel, tarmac, or snow stages hours before the first car, finding vantage points on berms, banks, and inside hairpins where they can see, hear, and feel the cars’ weight transfer and surface changes in real time. The appeal is proximity and authenticity: no grandstands, minimal barriers, and raw stagecraft. Preparation is a shared ritual.

Experienced spectators study organizer-issued maps and spectator guides, note stage closure times, and plan parking and footpaths to avoid closed junctions. They pack boots, layers, rain shells, headlamps for pre-dawn approaches, hearing protection, food, and fire-safe camp gear where allowed. Radios or event apps provide start lists, split times, and stage delays; many fans “stage-hop,” navigating legal liaison routes to catch multiple tests in a day. Service parks—open paddocks where teams work on cars—offer approachable access to crews, cars, and autographs.

Safety and etiquette underpin the culture. Marshals in orange vests mark prohibited zones with tape and signage and control crossings once a stage is live. Informed fans stand on the inside of corners or on high ground, never on the outside of fast bends or at the end of braking zones. Spectator drones are generally prohibited, and yellow flags at radio points can neutralize pace when incidents occur.

Under FIA regulations, spectators may push a stuck car back onto the road without penalty if it’s safe and no tools are used—common in snow events—but otherwise outside assistance is restricted. Local traditions give each rally its character. On Monte‑Carlo’s Col de Turini, night stages bring flares, horns, and candles along icy hairpins. Portugal’s Fafe jump draws thousands waving flags around the iconic crest, while Finland’s fast yumps reward fans who hike deep into the forest for multi‑apex views.

Argentina’s El Cóndor features wind, fog, and hillside asado, and Sweden’s banks turn crowds into ad‑hoc recovery crews digging cars free. Formerly dangerous behaviors—like the human “tunnel” crowds of 1980s Portugal—are now firmly banned and policed. There’s also a technical, collaborative side. Spectators trade GPS pins to safe viewing spots, cross‑reference historical pacenotes and onboard videos to predict lines, and track road order to anticipate evolving grip as sweepers clear loose gravel or snow.

Amateur photographers respect media zones and shooting angles dictated by course safety plans. Many events run spectator buses to reduce congestion, and volunteer marshals—often fans themselves—form the backbone of stage operations. The result is a fan culture that is immersive, knowledgeable, and integral to rally’s identity. It sustains rural economies during event weeks, amplifies atmosphere at legendary stages, and demonstrates that close access can coexist with modern safety—provided spectators follow guidance and self‑police.

This balance keeps rally unique among top‑tier motorsports: the world is the venue, and the crowd is part of the discipline that makes it possible.